This article has been updated with additional comment.

How easy should it be for terminally ill people to end their lives? Debate over how Oregon should answer that question is flaring in Salem.

A group of doctors want to cut the waiting period for Oregon’s Death with Dignity law from 15 days to 48 hours and allow not just physicians but nurse practitioners and physician assistants to prescribe medication and oversee the process that allows terminally ill patients to end their lives.

Critics say the changes will remove safeguards voters were promised when they approved Oregon’s physician-assisted dying law in 1994 and affirmed in 1997. Supporters, however, say the law needs an update in response to doctor shortages and for patients who are on the brink of death.

“I believe that these changes that are being proposed are not radical at all, and extremely reasonable,” Laurel Hines, a retired Salem social worker, told lawmakers Monday.

Lawmakers considered those arguments during a hearing of Senate Bill 1003, which would make the most far-reaching revisions to Oregon’s Death with Dignity program in the history of the law.

Hines said that Oregon’s law is modest compared to what’s in place in Canada and other countries. Without reforms to Oregon’s law, she said more people would turn to “do-it-yourself options.”

“I now have traumatic memories of my sister dying the way she did, and being in the condition she was and in pain that morphine didn't control and her loss of autonomy."

The Oregon Medical Association's vice president of government relations, Courtni Dresser, submitted written comments calling the waiting period reduction “drastic” and some of the bill's changes to the law confusing, dangerous and against the law's basic intent, raising concerns that it could unintentionally push Oregon closer to allowing “euthanasia.”

She questioned expanding the types of providers overseeing the law beyond physicians, saying they are best qualified to assess patients' conditions and evaluate their mental health. The law, she wrote, must use the “highest levels of training for those making these critical determinations.”

The bill “removes critical language requiring verification that a patient is capable, acting voluntarily, and making an informed decision,” Dresser added. “This verification is essential to ensure that vulnerable patients are not coerced or make decisions without full understanding. Removing this safeguard weakens patient protections and undermines the integrity of the process.”

Compassion and Choices, a nonprofit that supports Oregon’s law, is still analyzing the bill and will submit testimony later, spokesperson Marina Gephart told The Lund Report. Disability Rights Oregon declined to comment.

Number of physician-assisted deaths keeps growing

The Oregon Death with Dignity law, the first of its kind, was intended to give dying patients control over their end of life decisions and to reduce their suffering.

The law legalized physicians prescribing a lethal dose of medication to terminally ill patients. Its backers promised voters that its safeguards would ensure only competent patients capable of making their own decisions would use its provisions.

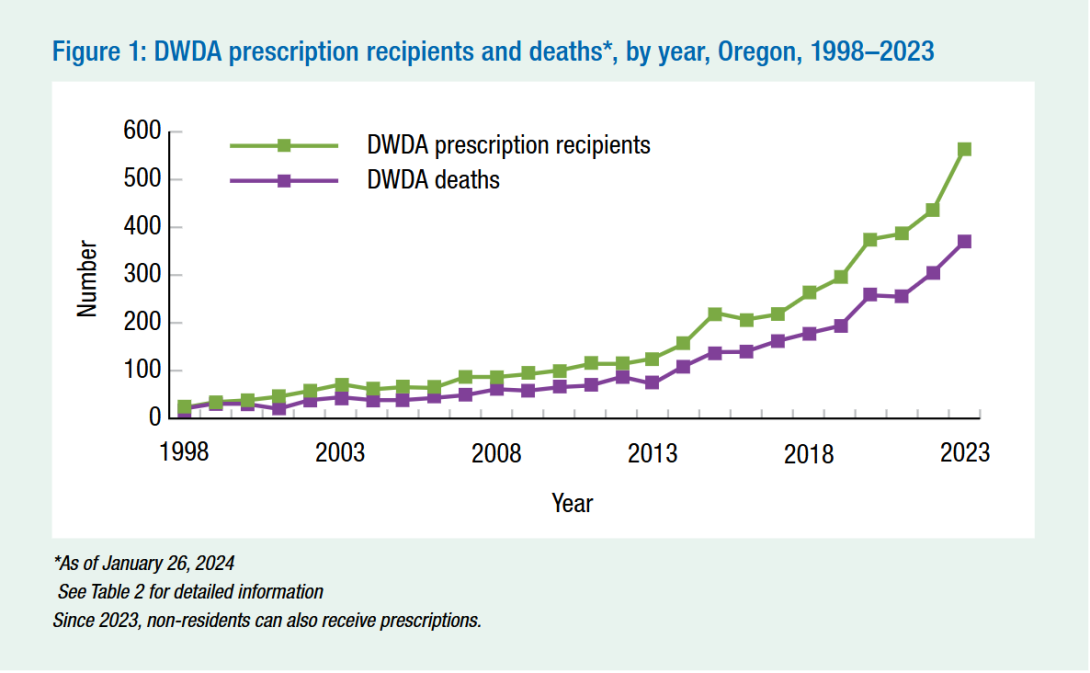

Since then, at least 2,847 people have used the law. In 2023, a record of 367 people reported ending their lives with medical assistance under the Oregon law, according to the most recent health authority figures.

That figure includes 23 people who traveled from other states to use Oregon’s Death with Dignity law. State officials said additional people from out-of-state may have used the law without reporting it.

The Oregon Health Authority in 2022 stopped enforcing the state’s residence requirements, which lawmakers formalized the following year as part of a legal settlement. That made Oregon the second state after Vermont with no residency requirement to access its physician-assisted dying laws.

Process, waiting period debated

To be eligible for Death with Dignity, patients must make two verbal requests separated by 15 days to their attending physicians for medical assistance in ending their lives. Their request must also be made in writing, which requires two witnesses to sign off on. A second consulting physician must also confirm the first physician’s determination.

The health authority in 2020 adopted rules that allowed people with less than 15 days to live to bypass the waiting period. SB 1003 would shorten that waiting period to 48 hours. The bill would allow physician associates and nurse practitioners to determine if a patient is eligible for medically assisted dying, including giving the second opinion.

“This bill makes it even easier for a broken health care system to suggest death as an answer."

Of the 10 states that allow for medically assisted dying, some have adopted similar changes to their laws. Colorado changed its waiting period to 48 hours last year. Washington in 2023 reduced its waiting period to seven days and allowed physician associates and nurse practitioners to prescribe medications. New Mexico’s law, passed in 2021, allows those professionals to prescribe medications.

“We are behind the times,” state Sen. Floyd Prozanski, a Eugene Democrat who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, told The Lund Report.

Prozanski said that for years he has heard from doctors such as Paul Kaplan, who help terminally ill patients end their lives who told him the law needs to be modernized.

Kaplan, a retired Lane County reproductive endocrinologist, told the committee that he is one of about 30 mostly volunteer physicians who work with nonprofit End of Life Choices Oregon to help patients access physician-assisted dying.

Expanding access to health care professionals is an appropriate response to the state’s physician shortages, he said.

“There are very large areas of Oregon where there is not a doctor available for hundreds of miles,” Kaplan said. “And so this service is literally not available to patients who live in those areas.”

But critics disagreed.

“This bill makes it even easier for a broken health care system to suggest death as an answer,” Sharolyn Smith, Oregon Right to Life political director, told the Oregon Senate Judiciary Committee on Monday.

Dr. Sharon Quick — president of the Washington state-based Physicians for Compassionate Care Education Foundation, which opposes physician-assisted dying — told lawmakers that the bill would put life-and-death decisions in the hands of ill-equipped professionals and leaves less time for patients to change their minds.

“This bill devalues patients suffering from disabilities, such as mental health problems, lack of capacity, psychological distress over loss of function that will not be uncovered due to inadequate time for assessment,” she said. “Nor is there time for patients to change their minds, which they often do.”

Quick, head of the Physicians for Compassionate Care Education Foundation, told the committee the bill would allow non physicians without relevant expertise “to make some of the most difficult medical assessments without a second opinion.”

Quick called on lawmakers to increase access to palliative care, which she said can ease the suffering of terminally ill patients who consider medically assisted dying. Such care would focus on the quality of the patient’s life, including minimizing suffering.

Streamlined process

The bill would allow physicians, physician associates and nurse practitioners to file reports and prescribe medications electronically, which they currently must do with paper. It would also require hospitals and hospice programs to disclose whether they will participate in Death with Dignity.

Proponents said the bill is meant to streamline the process for getting a second opinion on a patient’s determination. It would allow the second provider, which could include a physician associate or nurse practitioner, to sign a hospice program’s certification of their terminal illness.

Hines, the retired social worker, told the committee that reducing the waiting period is reasonable because terminally ill people can lose their ability to take the prescribed medications that will end their life within 15 days. She said that her sister died within a few days of being admitted to hospice for cancer.

“I now have traumatic memories of my sister dying the way she did, and being in the condition she was and in pain that morphine didn't control and her loss of autonomy,” she said.

But Angela Plowhead, a Salem psychologist, told the committee that 48 hours is not long enough for some mental health treatments like anti-depressants to take effect, which she said could make a patient change their mind.

She also said that 48 hours is not enough time to correct any misdiagnoses.

According to the state’s 2023 report, 560 people received prescriptions as of January 2024, but not all had taken them. Fifteen percent did not take the medications and died of their illness. It was unclear whether a quarter had taken their medications or not.

State figures show patients who used the law were overwhelmingly 65 or older and white, with cancer accounting for two-thirds of diagnoses and neurological diseases making up one in 10.

Nearly 90% of patients died at home and were enrolled in hospice care. The three most common reasons patients reported for seeking out medical assistance to end their lives included loss of autonomy, decreased ability to participate in enjoyable activities and loss of dignity.

Anabel Pelham, former head of the National Association of Professional Gerontologists (NAPG) and a former gerontology professor who sits on the Oregon Gerontological Association board, told The Lund Report that she could speak only for herself, not for any group. She supports expanding the types of professionals who can assist in the process, saying many regions in Oregon lack physicians, effectively placing access to physician-assisted dying off limits.

But she also noted that people can fluctuate between wanting to die and finding reasons to live.

Generally speaking, a waiting period of “48 hours seems very short to me,” she said. “I think the 15 days is probably appropriate.”