As independent primary care clinics continue to buckle under increased costs and low pay, an Oregon lawmaker says she has a way to help keep their doors open.

Sen. Lisa Reynolds, D-Washington County, is sponsoring Senate Bill 28, which is meant to strengthen the financial position of independent primary care clinics by requiring insurers to increase reimbursement rates to match those paid to hospital systems for the same services and care.

Reynolds has first-hand knowledge of the problem. A pediatrician at The Children’s Clinic, she said insurers pay her clinic significantly less for a routine check up for a six-month-old baby than what they would pay a hospital system for the same checkup. She said she is paid as much as 30% less after a day of seeing patients than someone working in a hospital system who performed the same services.

“We all have rent, we all have vaccine expenses, we all have payroll, right?” she told The Lund Report. “There’s nothing unique about what hospitals do when it comes to a six-month checkup.”

Oregon lawmakers have sought to broaden access to primary care, which research shows has long term benefits for patient health and costs. By targeting pay imbalances, the bill could have the biggest impact on Oregon’s primary care landscape this legislative session while giving modest help to small practices facing consolidation.

However, the bill is opposed by insurers. Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon, PacificSource Health Plans and Moda Health submitted written testimony arguing that “hospital rates may not be the best benchmark” and the bill would increase premiums for their plans’ members.

“Those health systems are really important. But there are a lot of physicians who want an independent clinic.”

Data shows that “hospital prices are incredibly variable” and hospital systems have demanded higher reimbursement rates from insurers because of a lack of competition, according to the testimony.

“While we are sensitive to the challenges that independent primary care practices are facing, we have significant concerns with paying them based on hospital prices, which are often inflated and well above market rates for other providers,” the insurers wrote.

Same service. Different setting. Different pay.

Reynolds, the Legislature’s only physician, said it’s becoming harder to make ends meet at The Children’s Clinic. She said costs around staff, electronic medical records and others are up, while pediatricians and other primacy care remain among the lowest paid medical specialties. She’s not alone.

During a hearing earlier this month, Reynolds cited a Congressional Budget Office report showing the financial headwinds facing independent clinics.

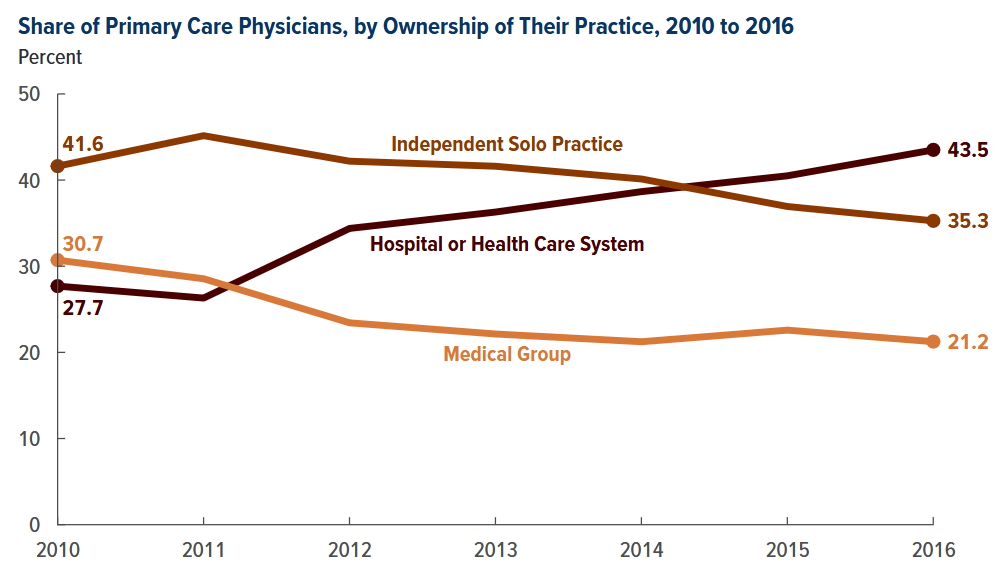

The percentage of primary care physicians employed by a hospital or other health care system increased from 28% to 44% between 2010 and 2016, according to the report. Meanwhile, the share of primary care physicians working in either a solo practice or as part of an independent medical group declined.

Echoing a longtime complaint of experts, the report suggested that one driver of the takeover and consolidation trend in primary care is that Medicare and commercial insurers pay higher prices for outpatient services that are billed by a health system rather than by a clinic or physician’s practice.

Reynolds told The Lund Report that she learned about the pay discrepancy during earlier discussions she had with providers and others about Oregon’s efforts to improve primary care and the challenges facing independent clinics. She began researching the topic.

“And I just came up with this idea of equal pay for equal care,” she said.

The role of independent clinics

Large swaths of Oregon are designated as having shortages of primary care professionals. Between 2014 and 2019, Oregon saw a 13% decline in the total number of primary care clinicians working in the state, according to advocacy group Primary Care Collaborative.

Over the last decade, lawmakers have passed legislation intended to ensure access to primary care. That includes requiring insurance companies to assign primary care providers to members without one and to spend at least 12% of expenditures on primary care by 2023. Lawmakers also directed the state to convene the Primary Care Payment Reform Collaborative, an advisory group.

Betsy Boyd-Flynn, executive director of the Oregon Academy of Family Physicians, told The Lund Report that it’s important to have a variety of primary care settings so that physicians can practice how they want.

“Those health systems are really important,” she said. “But there are a lot of physicians who want an independent clinic.”

Reynolds said the 25 physicians at her clinic have more control over their work and could decide, for example, to have a flu shot clinic on a Saturday. She also texts with patients, including a recent exchange with a mother worried about her child’s seizures.

“We all have rent, we all have vaccine expenses, we all have payroll, right?”

Regence shares lawmakers’ concerns about the long-term viability of independent primary care practices, spokesperson Dean Johnson told The Lund Report in an email.

“However, there is a much larger conversation needed about primary care viability and reimbursement rates,” he wrote.

Bigger discussion

All of SB 28’s provisions come from an amendment that was published on April 8, the same day the Senate Health Care Committee approved the new language and advanced the bill ahead of a legislative deadline around the session’s halfway point.

The insurers argued in their testimony that the bill “takes on too much at this juncture in the legislative session” and will not address “how to ensure fair reimbursement rates for all primary care services, regardless of setting.”

The bill would result in higher premiums with the average Oregonian paying $120 more and the average family of four paying $480 more each year, according to Regence.

Reynolds said her bill is a “stopgap” and she wants to have bigger discussions around primary care and hospital finances. She acknowledged that her bill likely will cause some financial strain for insurers, but more spending on primary care will pay off in the long run.

The bill would direct state regulators to adopt an annual primary care benchmark reimbursement rate that is based on the highest rate reported by a hospital system in the appropriate geographic market.

Regence criticized the bill for only applying to commercial health plans and leaving out those that cover state workers.

The bill does not apply to government health plans, including the Oregon Health Plan. Reynolds said she wanted to minimize the bill’s price tag, which she said will include the cost for regulators to set the rate.

The bill is currently in the Legislature’s budget-writing committee.

You can reach Jake Thomas at [email protected] or at @jthomasreports on X.

Dr Reynolds is exactly right! Interesting how Regence is quick to criticize the bill....when they have one of the widest gaps between what a hospital system well child exam is paid vs. an independent clinic well child exam. Oh, and they don't even have a way to contact anyone about contract renegotiation - it's take it or leave it. If we don't do something soon to stop the mass exodus of primary care providers in Oregon, our Urgent Care centers and ER's will be overrun with non urgent and emergency care because people have no where else to go.